Paul Harvey and Pamela McCormick – UK lawyers in the Registry of the European Court of Human Rights – talk to RightsInfo about interpreting the UK’s European Court of Human Rights statistics.

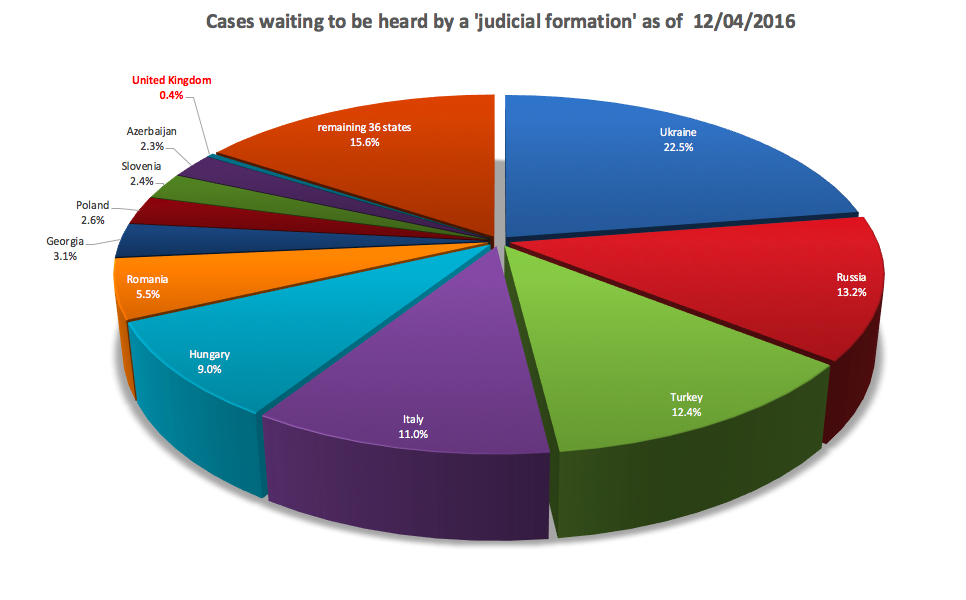

Adam Wagner and Rebecca Hacker’s recent post – 4 Charts Which Show The European Court Of Human Rights Has Dramatically Changed Its Approach To The UK – makes a number of excellent points interpreting the drop in the number of UK cases pending at the European Court of Human Rights. Since the Court’s statistics are not always easy to interpret, this post seeks to explain the numbers, specifically the fact that only 0.4% of the Court’s pending cases concern the UK.

First, a preliminary remark. The UK statistics are best read alongside those from comparable countries. It is instructive to compare the UK with France and Germany – obvious comparators given their size and status as well-established democracies. The UK has consistently had slightly fewer cases per head than either of these countries.

Excepting prisoners voting cases (the “outliers” as RightsInfo’s previous post correctly describes them), the number of violations found against the UK is lower than either country. 2015 saw 4 violation and 9 no violation judgments in respect of the UK. France had 17 violation and 10 no violation judgments and for Germany there were 6 judgments finding a violation and 5 finding no violation.

Explaining the trend

We think there are three reasons for the drop in number of UK applications to the Court and in the number of violations.

First, the Court is, across the board, much stricter in determining what constitutes a valid application to the Court. Any application which does not meet the requirements of Rule 47 of the Rules of Court is administratively rejected. Approximately half of prospective UK applications fail at this stage. That strict approach is beginning to have a real effect on the Court’s backlog of cases.

Second, there is the effect of the Human Rights Act 1998. The Act means that more cases are resolved at the domestic level and, for cases that do come to the Court, it has the domestic court’s views before it decides. This makes it less likely that the Court will find a violation, since this would mean rejecting the domestic courts’ conclusions. Given the full and conscientious consideration which the UK’s superior courts give to human rights cases, very few result in violations. When violations are found, it will often be where the domestic courts themselves have disagreed (see, for instance, the disagreements between the Court of Appeal and the House of Lords (now the Supreme Court) in M.H. v the UK and Othman v the UK).

Third, because the Human Rights Act allows people to rely on their rights in any domestic legal proceedings, the Court has taken a much stricter approach to the requirement that a claimant must exhaust all domestic remedies. See, for example, Peacock v. the UK, which the Court declared inadmissible because the applicant had not explicitly argued his right to enjoyment of property before the domestic courts. It is not sufficient either to invoke a general right or to invoke a Convention right “in substance”. Applicants now have to expressly argue the Convention in domestic proceedings.

Where do the 0.4% come from?

In the controversies surrounding the Court and the UK, it is often forgotten that the majority of UK cases before the Court concern technical questions of law that only lawyers could love. They are mostly complaints under Article 5 (the right to liberty) and Article 6 (the right to a fair trial) of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), such as claims concerning the length of immigration detention or the fairness of a criminal trial. Many would say this is the proper work of courts, whether domestic or international. The headline-making cases, where the Court is called upon to examine the compatibility of an Act of Parliament with the rights in the ECHR, are vanishingly rare.

While we make no comment on the degree of influence the Court has on the UK, what is seldom appreciated is the extent of the UK’s influence on the work of the Court. No legal tradition had a greater impact on the drafting of the ECHR, nor its subsequent interpretation by the Court, than the common law. That influence continues: judgments of UK courts are widely read and considered at the Court, not just in cases against the UK, but in cases against other countries too. This is made possible by the UK courts’ ability, through the Human Rights Act, to consider (and where necessary criticise) the Court’s case law.

It means that the UK cases before the European Court of Human Rights – the 0.4% – buy the UK a great deal of influence over the proper development of the ECHR system, both at the Court and across Europe.

Paul Harvey and Pamela McCormick are UK lawyers in the Registry of the European Court of Human Rights. The views expressed are personal.