Julian Assange has been back in the news, with the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention “deeming” his detention to be arbitrary. The reaction from human rights experts has been… mixed. What does it all mean?

Who is Assange and what is Wikileaks?

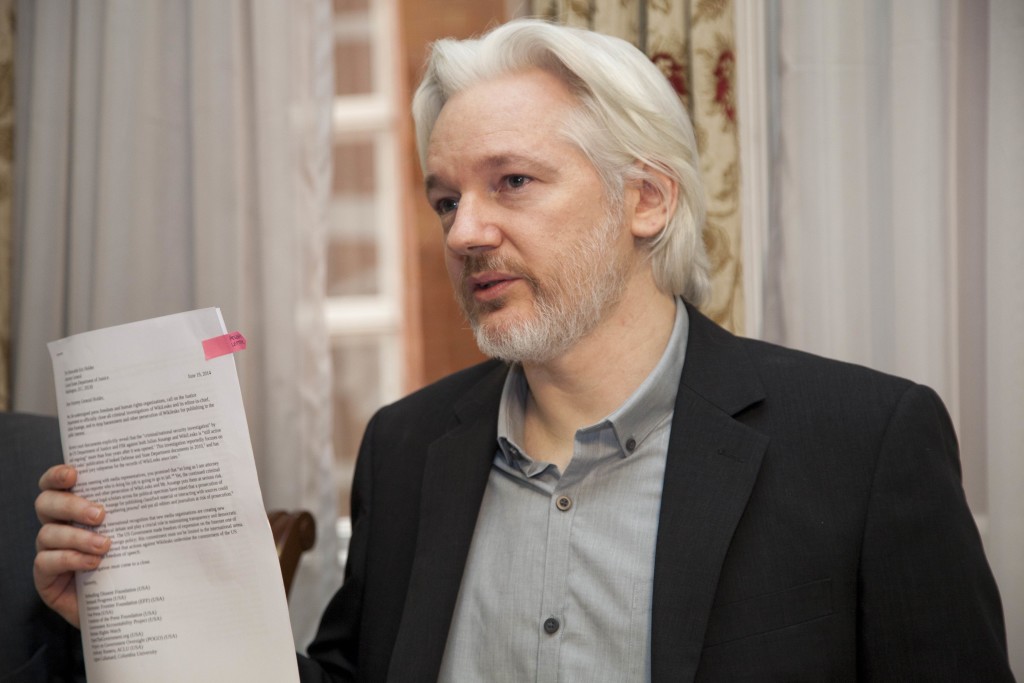

Julian Assange is an Australian journalist, founder and editor-in-chief of Wikileaks. He has made headlines around the world for years now. This is not surprising. Ever since Assange founded Wikileaks in 2006, as many as 8.5 million confidential governmental files and documents – including the famous “Collateral Murder” Video, the Afghanistan and Iraq war logs as well as the Guantanamo Files and documentation of Obama administration’s pressure on other states not to prosecute Bush-era officials for torture – have been published on his website.

What is the case against Assange?

In September 2010, a Swedish prosecutor re-started an investigation against Assange on allegations of sexual misconduct that had previously been dropped in August. Assange had allegedly committed the sexual molestation and unlawful coercion of two women he had had sex with on a visit to Sweden that summer. Sweden issued an International Arrest Warrant and Assange was arrested in the UK by British police and was detained in Wandsworth prison for 10 days. His supporters raised the money for him to be released on bail and Assange started fighting the extradition warrant in British Courts (claiming he was at risk of being extradited from Sweden to the US, where he would be denied a fair trial under draconian espionage laws).

His case and appeals were unsuccessful and in 2012 he broke his bail conditions to flee to the Ecuadorian embassy in London. The case against him has appeared to lose momentum since then. Three of the four alleged offences have been dropped but he is still wanted for questioning over the allegation of “lesser degree rape”. He has never been formally charged, as – according to Swedish legal procedures – he would have to be questioned in order for this to happen. Negotiations between the Swedish, British and Ecuadorian authorities to arrange for an interview to take place in the Ecuadorian embassy have been unsuccessful so far although his questioning may happen in the future.

Why is Assange living in the Ecuadorian embassy?

On 14 June 2012, the UK’s Supreme Court rejected Assange’s final appeal against his extradition to Sweden. Five of the seven justices decided that the European Arrest Warrant, which obligates the UK to extradite Assange to Sweden, was valid.

Six days later, Assange broke his bail condition and walked to the Ecuadorian embassy, seeking political asylum. While there, police encircled the building and Assange was forced to stay. The Ecuadorian Embassy granted him “diplomatic asylum” (a concept not accepted by the UK) in August 2012 and he has been living in an 18 m² apartment inside ever since. He hasn’t left because Scotland Yard has kept the embassy under 24-hour surveillance (spending up to £13 million until October 2015and subsequently keeping it under ‘covert’ surveillance) – in order to be able to arrest him as soon as he steps outside Ecuadorian soil.

What is the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention and what did it say?

The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) is a specialist UN body made up of five independent human rights experts. It investigates alleged cases of arbitrary detention and writes its opinion on them. The States involved have to take these Opinions into “due consideration”. These are considered to be “quasi-judicial”: the is, they produce what look like legal decisions but are not legally binding on states – in other words, the state is not obligated to follow the opinion.

On 5 February 2015, the WGAD publicly released its Opinion on the Assange case. In its 17-page Opinion, the panel concludes that Assange is being arbitrarily detained by Sweden and United Kingdom, and it calls on them to immediately end this deprivation of liberty and pay him compensation. Specifically, the working group has declared that Assange’s detention is “category III” arbitrary detention, where detention is arbitrary because of a serious non-observance of the right to a fair trial.

How have people reacted to the UN Opinion?

Reaction has, to put it mildly, been mixed.

Some saluted the decision as “a major legal victory for international human rights law”, highlighting the plight of whistleblowers and marking an important development in the law of detention by expanding the remit of de facto detention (that is: someone is detained when he is forced to choose between confinement and running the risk of persecution). Assange himself has called it ‘a victory that cannot be denied’ and human rights groups have firmly stood behind the Opinion and the WGAD itself.

Other are unconvinced. How could the UN get it so wrong on Julian Assange?, Joshua Rozenberg asked. The main argument here is that it is difficult to say that Assange has been ‘detained’ in the Ecuadorian embassy – and still less that his detention was of an ‘arbitrary’ character – as he has always been free to leave the diplomatic premises. WGAD’s legal reasoning is supposedly “thin, to say the least”.

Other issues with the Opinion are: it considers Assange’s 10-days solitary detention in Wandsworth prison as arbitrary on the precarious grounds that “arbitrariness is inherent in this form of confinement”; it improperly terms the period of time in which Assange was living at home under strict bail conditions which included monitoring through electric tag and a ban on being outside at night as “house arrest”. Significantly, it fails altogether to articulate how Sweden and Britain can be said to be Assange’s ‘detainers’ and how his prolonged residence in the Ecuadorian embassy is to be considered as detention when he could (supposedly) leave voluntarily.

In summary, the Opinion provides no real justification for seeing Assange’s stay at the embassy as an ongoing deprivation of liberty rather than the voluntary confinement of a “fugitive from justice”. So unsound are these legal premises, they say, that the same argument would not hold before the European Court of Human Rights.

While legal commenters were busy discussing the Opinion’s supposed legal flaws, news of the WGAD Opinion went viral on social media, with many Twitter users mocking the panel’s large interpretation of detention.

What has been the reaction of the governments involved and what will happen next?

What has been the reaction of the governments involved and what will happen next?

Both Sweden and the UK have rejected the WGAD Opinion and announced a formal contestation. Swedish authorities have denied having any control over Assange’s decision to leave the Ecuadorian embassy and their British counterparts have mounted a vocal critique, the UK Foreign Secretary branding the panel’s Opinion as “ridiculous”.

As for what will happen now – well, that really is a big question. For the moment, nothing has changed: with the British and the Swedish governments remaining firm in their positions, Assange remains inside the Ecuadorian embassy.

This piece was written by Corallina Lopez-Curzi, a member of the RightsInfo volunteer team