Warning – spoiler alert! This post contains information about the Netflix documentary series Making a Murderer.

As well as turning viewers into armchair investigators and aspiring lawyers, the series highlights some hugely important and, at times, deeply troubling human rights issues.

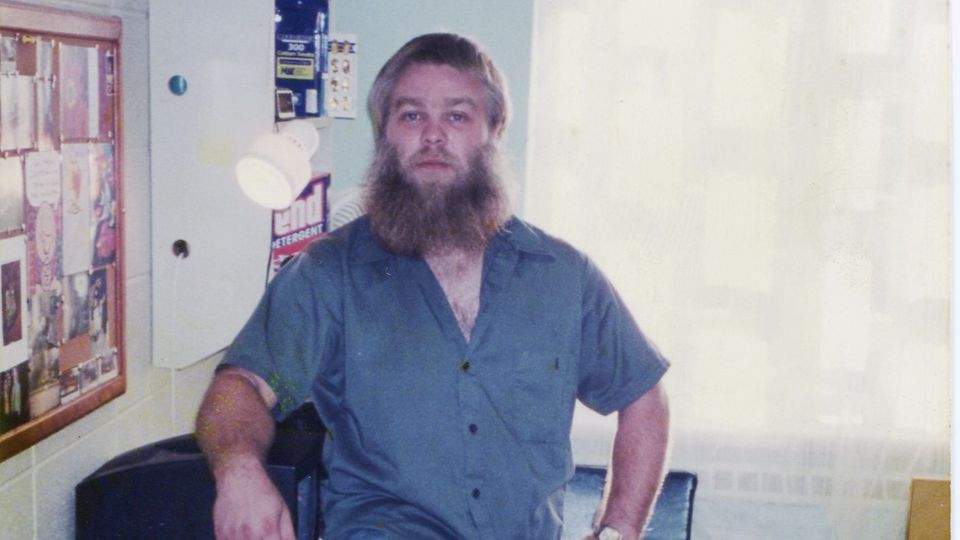

The documentary follows Steven Avery, a man from Wisconsin, USA, and his run-ins with the US criminal justice system.

Steven Avery was first accused of attacking a woman on a local beach in 1985. He protested his innocence but a jury found him guilty of sexual assault, attempted murder, and false imprisonment. He served a staggering 18 years of his sentence in prison before DNA evidence proved that he had not in fact committed these crimes. In a separate case in 2007, Steven Avery was convicted of murdering a woman, Teresa Halbach, and was sentenced to life imprisonment. Avery’s nephew, Brendan Dassey, was also imprisoned for involvement in the murder.

So, what’s all the fuss about?

Well, several things about this rang alarm bells:

- 1. The fact that the police officers from Avery’s first (wrongful) conviction, and whom he was suing for millions of dollars, continued to be involved in the 2007 case. (The words ‘biased’ and ‘corrupt’ were thrown around a lot);

- 2. How to make sure that poorer people can afford decent defence lawyers (a genuinely sad state of affairs); and

- 3. The damaging effect on Avery’s presumption of innocence when the media broadcasted the prosecution’s gory version of events before the trial.

But of all the issues which the documentary raises, perhaps the most troubling is the treatment of Steven Avery’s teenage nephew, Brendan Dassey, at his police interviews.

Brendan is often questioned alone by police investigators. The interviews last several hours. Eventually, questions and prompts elicit from Brendan a form of confession, incriminating both himself and Steven Avery. Brendan later went back on his statements, saying that the police had ‘got into his head’.

Brendan was just 16 years old at the time of the interviews. He had an IQ of around 70, which is on the borderline for intellectual disability. He was introverted and the versions of events which he presented were often inconsistent, giving the impression of someone confused or intimidated.

It’s a difficult watch. Brendan Dassey was, on account of his youth, isolation and mental deficiency, an extremely vulnerable person. It is difficult to accept that he could have been questioned without a defence lawyer or other responsible adult present. Several commentators have noted that vulnerable people, especially teenagers, subjected to this kind of interrogation are more susceptible to making false confessions (see, for example, here and here).

But this is just in the US, right?

Nope. Across the pond, a vulnerable person’s right to communicate with their lawyer or a responsible adult formed part of a recent case before the European Court of Human Rights.

In R.E. v United Kingdom, a young person (R.E.) was arrested in connection with the murder of a Police Constable. R.E. was assessed by a medic to be a ‘vulnerable person’ within the meaning of the Terrorism Code of Practice. This meant that R.E. could not be interviewed, apart from in exceptional circumstances, in the absence of an ‘appropriate adult’, i.e. a relative or guardian, or a person experienced in dealing with mentally vulnerable people. Despite this, R.E. was in fact interviewed by police officers without a solicitor or appropriate adult present.

Following R.E.’s later re-arrest, R.E.’s solicitor asked for an assurance that their discussions would not be subject to secret surveillance by the police. The authorities refused to give that assurance. The Court decided that surveillance of a person’s discussions with their lawyer was an extremely significant intrusion into the right to respect for privacy. There were not adequate protections in place and so there had been a breach of R.E.’s rights.

Fascinating this human rights stuff, isn’t it?

Making a Murderer has brought increased human rights awareness to the masses. People who would not normally talk about human rights issues are discussing them at work and debating them on social media. After seeing footage, many have thought ‘surely this can’t be right’. They care. And that is what defending human rights is all about.

This post is by Natasha Holcroft-Emmess, a RightsInfo volunteer