Today is the International Day of Remembrance for the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

On Slavery Remembrance Day, we remember those who suffered through the brutal historic slave trade. But we also raise awareness of human trafficking: a modern slave trade that currently happens around the world.

What was the transatlantic slave trade?

From the early 1500s until the mid-nineteenth century, over 12 million men and women were transported from Africa to be sold as slaves in the West Indies and South America, as part of a horrific cycle that became known as ‘Triangular Trade’.

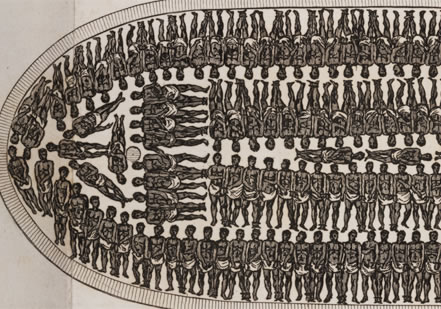

Ships brought goods from Britain to trade with West Africa in return for slaves. The ships then took slaves across the Atlantic Ocean to be sold for profit and put to work on the enormous plantations, owned by colonisers, to grow sugar, tobacco and cotton. These products were then shipped back to Britain to be sold.

During the Atlantic crossing, slaves were kept naked, chained and cramped together for weeks on end with very little food. Disease was rampant. It is estimated that 12.5% of slaves died before the ships even docked: that’s around 1.5 million people.

And for those who survived, a life of brutal slavery awaited them. Slaves were kept as property, beaten, raped and made to do back-breaking labour. Prominent English politician and slave trade abolitionist campaigner William Wilberforce estimated that the overall mortality rate was around 50%.

How was slavery eventually abolished?

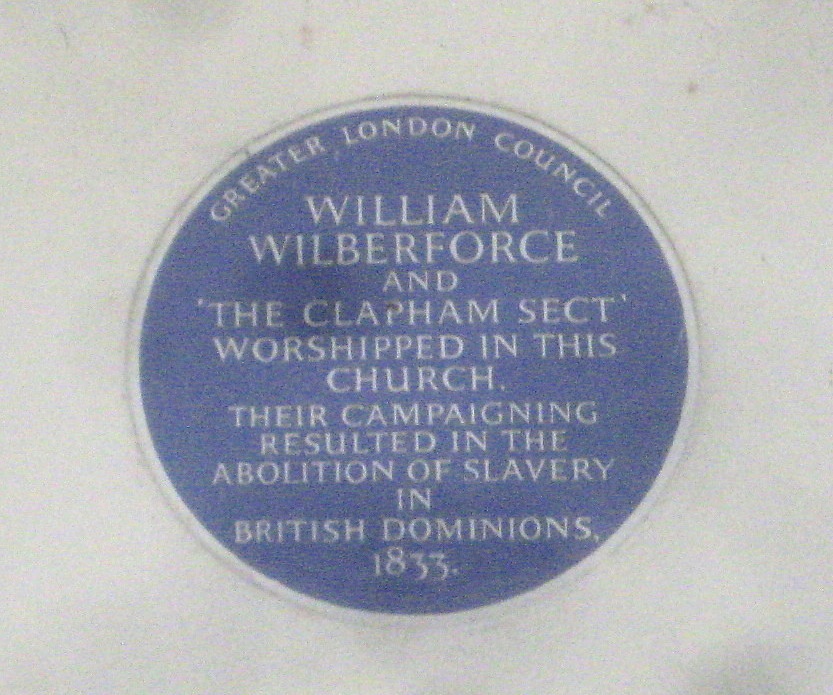

It took decades of effort to abolish slavery in British law. Most famously, William Wilberforce, along with fellow members of the evangelical Christian group ‘the Clapham Sect’, campaigned tirelessly for the abolition of the slave trade.

Women also played a key part in the abolitionist movement. Women used their role as consumers to boycott goods that were produced by slaves, such as sugar and cotton. They formed anti-slavery societies, like the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves, which organised petitions, public meetings and sent money to schools in the West Indies.

Between 1789 and 1805, 9 anti-slavery bills, spearheaded by Wilberforce, went through Parliament, but were all defeated. Finally, in 1807, the Slave Trade Act abolished the slave trade in the British Empire.

However, although the slave trade was abolished, it was not until the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 that the institution of slavery itself was finally abolished throughout most of the British Empire.

So, slavery is gone for good now, right?

Sadly not. On 25 March 2015, the UN unveiled a memorial at their headquarters in New York, to remember the victims of the transatlantic slave trade. But slavery did not really end in 1807, or 1833.

Assessments vary, but the 2014 Global Slavery Index estimates that 35.8 million people around the world are trapped in slavery today. That’s nearly 3 times the number of people caught up in the transatlantic slave trade over a 400-year period. Benjamin Skinner, a fellow at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy at Harvard Kennedy School of Government, says: “There are more slaves today than at any time in human history.”

The UK Home Office predicts that there may be as many as 13,000 victims of modern slavery in the UK alone. The presence of modern slaves in countries like the UK is largely a result of human trafficking.

Which laws protect people from modern slavery and human trafficking?

The Protocol to Prevent, Suppress and Punish Trafficking in Persons (part of the UN Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime) requires States to establish “trafficking in persons” as a criminal offence in their domestic law.

In the UK, a recent Act of Parliament consolidated existing laws criminalising slavery and people trafficking. The Modern Slavery Act 2015 details the criminal offences of arranging the travel of another person with a view to them being exploited; holding someone in slavery or servitude; and forcing someone to perform compulsory labour.

The Human Rights Act 1998 (which gives effect to the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) in UK law) prohibits slavery in the UK. Article 4 ECHR states “No one shall be held in slavery or servitude. No one shall be required to perform forced or compulsory labour.”

Human rights have, on several occasions, provided enhanced protection in the UK for victims of human trafficking. You can read some examples of this here and here.

Dreadful, but irremediable?

The transatlantic slave trade was once described by William Wilberforce, in his 1789 ‘Abolition Speech’ to Parliament, as “so enormous, so dreadful, so irremediable”.

The problem of modern slavery is still enormous, and still dreadful, but thanks to decades of campaigning, dedication and legislation, it is not necessarily irremediable. And let us never forget Britain’s involvement, in the past and the present.

You can learn more about how to get involved in the fight against slavery through charities such as antislavery. Read more about the prohibition on slavery here. Take a look at our resources on protecting people seeking refuge here and treating all humans equally here.