Natasha Devon MBE tells RightsInfo about growing up with a chainsaw-wielding mum, rethinking ambition, and being failed by the mental health system.

“The waiting list at the moment for children and adolescent mental health services is between 6 months and 2 years,” Natasha Devon tells me, “which is just an eternity.”

Few people are better placed to understand how young people struggle in the mental health care system. In 2015, the Department for Education appointed Devon as its first mental health champion for schools. She was sacked just one year later, she tells me, for her refusal to toe the government line.

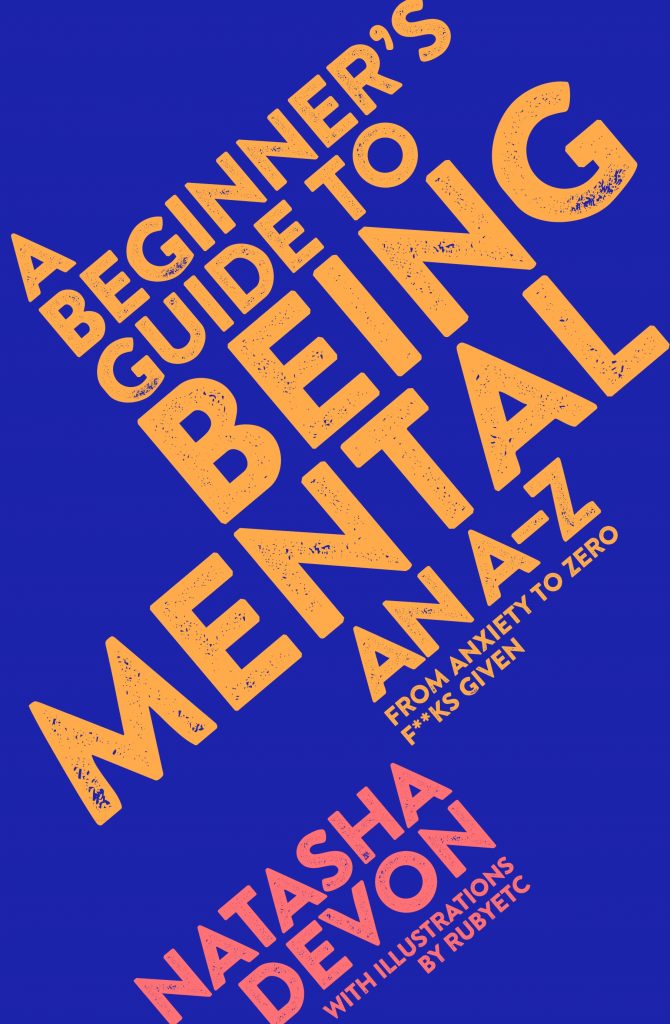

A writer and activist, Devon now tours schools talking about issues that range from mental health to body image. She also has a new book out called A Beginner’s Guide to Being Mental: An A-Z. Devon used the book to speak out about her own experience of anxiety and an eating disorder. She also argues that when it comes to mental heath, too many people are going without adequate care.

She tells RightsInfo about her memories of a chainsaw-wielding mum and why education and free healthcare are so important.

What did you want to be as a child?

I went through lots of different phases but I definitely knew that I wanted to do something on the stage. I really loved dancing but unfortunately, I do not have a talent for it. I don’t know if you remember there was that advert on TV a couple of years ago where there was a girl knocking things over? My mum said that was basically my childhood.

Image courtesy of Natasha Devon. All rights reserved.

How did your education shape you?

I would not be where I am without my education. I come from a very working-class background and I got into a good comprehensive school. But I was outside the catchment area, so I got in on academic merit. Knowing what I know now about how different schools can be, I just can’t imagine a better school for the type of person I am. I was just given so much encouragement and was taught a curiosity and love of learning. I don’t remember any of our teachers ever saying, “this isn’t on the exam so we can’t discuss it.”

What’s the most important lesson your parents taught you?

From my mum, I learned just how capable a person can be and that you don’t have to conform. My mum was a single mum for a quite big chunk of my childhood, and I never felt like I wanted for anything. I remember her cutting the hedge in the back garden with a chainsaw while wearing hot pants. That kind of sums up my mum, she’s just so capable and she never thinks she can’t do anything. I think I got that can-do spirit from my mum.

You mention in your book that your anxiety started as a child. How did your parents respond?

Well, it was both normalised and not talked about at the same time, if that makes sense? I can now see traits of mental illness in other members of my family so, in some ways, it’s just kind of how we work. But because we didn’t have the language or the understanding that we have now, it was not talked about in ways that were helpful to me. I can’t tell you the relief when I finally got a diagnosis of anxiety, and [thought], “it’s not just that I’m worse at coping with life that everyone else.”

Nature or nurture?

I think nurture is more important but nature is something that you can’t ever disregard. There was a massive 20 years chunk of my life where I didn’t see my biological father and I met up with him as an adult, having not remembered him from my childhood, and we had similar hand gestures and facial expressions.

I couldn’t have learned those. If you’d asked me before I reconnected with him, I would have said, “nurture all the way” but now that’s driven home to me that some stuff is inherent.

Image courtesy of Natasha Devon. All rights reserved.

What’s your best memory?

I have two childhood toys that I’ve kept to this day and one of them is a teddy bear called Isaiah. On the TV there was this advert for Kodak films. If you bought, I think seven Kodak films, you got a free teddy bear. The way that they made it look in the advert is like this massive plush bigger-than-you fluffy gorgeous thing. So my granddad who is just a really wise kind man – he saved up seven Kodak films.

My mum was a single mum for a quite big chunk of my childhood, and I never felt like I wanted for anything. I remember her cutting the hedge in the back garden with a chainsaw while wearing hot pants.

Natasha Devon

It was a big event, you know: “we’re going to Boots to get you your free teddy bear!” I still remember now that there was this big bin behind the counter with all these teddy bears in a sort of goldfish plastic bag. This guy, who could only have been about 16, just sort of slung it at me. And I was like, “oh, this teddy has a wonky face.”

Even at that age I thought, “I don’t want to act disappointed because I know my Granddad’s worked really hard,” but I’ve never have had a face where I can hide anything. So my granddad said “you know, no one else has got one like that? Because he’s got a wonky face, that’s totally unique.” It taught me that these things that we think of as imperfections are actually the things that make us special.

What human right do you value the most?

It would either be healthcare or education. If you keep someone healthy and educate them then I feel like everything else sorts itself out. It goes so far in addressing inequality, it gives people opportunity, it enhances the quality of their life. They’re the two cornerstones of the kind of society I would be proud to be part of. And I also feel like they’re both currently under threat.

What’s a lesson about human rights that you learnt the hard way?

Access to healthcare for your mental health is definitely something that I’ve learned the hard way. Whenever I’ve gone to A&E or my GP for a physical health problem, it’s been dealt with professionally and swiftly. With mental health problems I’ve been let down – first of all by having my eating disorder dismissed because my BMI wasn’t low enough. Then, second of all, by being given sessions [with a] CBT practitioner [who] didn’t understand the difference between me grasping it in theory and being able to put it into practice.

I feel like I’m very lucky in that I was then able to go: “okay, I’m going to find myself a private therapist, this didn’t work.” But I think about all the people who aren’t in a position to do that.

What would you save your house in a fire?

I mean…my husband, but that kind of goes without saying, doesn’t it?

With mental health problems I’ve been let down.

Natasha Devon

My Great Granddad was in the Second World War and he had this truncheon that could kill a person. He gave it to my mum when she was a single-mum, because my mum is hot! He said, “a woman that looks like you and lives alone needs a weapon.” Then, when I moved out, my mum passed it down to me. So I would probably say that. I need to go out looking for someone who lives alone that might need it!

What surprises people about you?

I think people are surprised that I have anxiety, if they don’t know. Because things that should freak me out don’t and then it’s the little things that I struggle with. I obviously have bad days as well but, because I’m confident, and confidence and anxiety are two separate things, they go: “oh I never would have thought, you.”

Image courtesy of Natasha Devon. All rights reserved.

What does ambition mean to you?

I think ambition is something that very easily turns into envy. Particularly in the kind of society that we live in. It’s consumerist capitalism, isn’t it? You’ve always got to have more. So I think while having ambition is important it’s also important to keep it in check.

Are you a believer, atheist or agnostic?

I think the only sensible way to be is agnostic. I’m not religious and I don’t believe in God in the way that it is traditionally defined. But I also think it’s incredibly arrogant to assume that modern science and empiricism either can or will find the answer for everything. Because the human brain is incredibly limited, it’s brilliant but it’s limited, and we’re only experiencing tiny corners of the available reality. There is so much that is invisible to us and unfathomable.

What is the meaning of life?

I think it’s to be fair and kind.