Hope Virgo was 13 when she first began to suffer from anorexia. After four years of hiding the illness, she finally received successful treatment, but after several years in recovery, she relapsed in 2016. When she reached out for help, she was initially told she wasn’t thin enough to be treated.

“People often think that it’s just a teenage girl’s illness, she tells RightsInfo, “but it affects guys, it affects older people and people from all different backgrounds as well.”

Now a mental health campaigner and author of her own book Stand Tall Little Girl, she works with schools, businesses, and the NHS to raise awareness around eating disorders, a subject she says is all too often misunderstood.

“I think it’s partially the way that the NHS funds stuff,” she explains. “If you’re not really underweight it’s difficult to get that support. So when I relapsed I wasn’t able to get support even though I’d already been in hospital once in my life – because I wasn’t thin enough. People think that if you have anorexia as soon as you start eating you’re fixed. But your mind will take so much longer to catch up than it will for your body to change shape.”

It was a relapse in 2016, following the death of her grandmother, that led Virgo to write her book. “I realised that there’s a serious lack of support available for adults with eating disorders unless you’re at that critical point,” she explains. “I also realised that I was too embarrassed to admit that I was struggling. I wanted to write my book to raise awareness of mental health more broadly, but also to get rid of all of the myths that come with eating disorders.”

She tells me about the long road to recovery and what gets left out of the conversation about mental health.

Image Credit: Hope Virgo / Twitter

Image Credit: Hope Virgo / Twitter

What did you want to do or be as a child?

I wanted to be an athlete, actually. I really liked long distance running and thought I was quite good at it. I blame that I got an eating disorder for the fact that I didn’t become an athlete. But I probably also wasn’t good enough to be one! That’s my excuse.

How did your education shape you?

Being at an all-girls school, I really struggled with the pressure to be a certain way and to look a certain shape. Instead of getting preoccupied with that, I just flung myself into all the sport at school so that I’d able to just wear my sports kit every single day.

People often think that it’s just a teenage girl’s illness, but it affects guys, it affects older people and people from all different backgrounds as well.

Hope Virgo

What’s the most important lesson your parents taught you?

To be honest with people. To have that honesty and to keep being honest with people that you’re close with and to not lie about anything.

Do you think that helped you with anorexia?

No, weirdly. I think that [what] anorexia did to me, and what it does to a lot of people, is you become really deceitful. You lie, and you shy away from everything. You don’t want people to know what’s going on because you don’t want people to take away that anorexia from you.

But since recovering, I make sure that I’m really honest. If I’m struggling and doing too much exercise or I have a day where I’m counting my calories, I feel the need to tell people because otherwise I feel guilty that I’m not being honest about it.

Hope Virgo has now become a prominent campaigner. Image Credit: BBC News

Hope Virgo has now become a prominent campaigner. Image Credit: BBC News

What is your best memory?

Probably when I was travelling. I spent a year volunteering in the middle of nowhere in Thailand with a group of kids. They had a children’s home there and the children had all been abandoned or lost their parents. We used to sit out most days with the kids and there was no pressure whatsoever. It was such a big part of my recovery and I loved spending time with them.

How did it help your recovery?

I liked being out of England, where I couldn’t count calories, where I had no idea what I was eating, and I lost all that control. I also couldn’t exercise quite as much because it was unbearably hot and there wasn’t really an exercise area. It helped me get away from that regimented institutionalised lifestyle that I’d been living. When I was in hospital, I became so fixated on breakfast, snack, lunch, snack, dinner, snack and that was my day.

It’s about having no fear about trying to get places.

Hope Virgo

I found it very difficult to break that [habit] but, travelling and being away, I didn’t have a choice because I didn’t know when the food was coming. When I got there, I was quite nervous about it but I learnt to switch off and realise (it sounds really lame) there was so much more to life – and so much more to the world than being so fixated on everything I was eating and all the calories.

What does freedom mean to you?

Being able to do what I want to do when I want to do it. And being able to say what I want to say without judgement. On a more societal level, it’s about people having no fear about trying to get places. I do quite a bit of work in Calais with all the refugees, and I find it so frustrating that, because of where I was born, I can just cross into any country. I think if we lived in a completely free society, we’d find a way to support all of these people.

Image Credit: Dylan Brethour / RightsInfo

What human right do you value the most?

Probably freedom of travel, making sure people who are in a really difficult situation aren’t just left in the lurch. I struggle with the fact that a lot of [the refugees] will have mental health problems, and their rights have just been stripped. We live in England and we get treatment through the NHS, but these people are just stuck there with nothing.

What is a lesson that you’ve learned about human rights the hard way?

I think we should do more for people’s mental health rights. When I relapsed, I ended up going on anti-depressants just for a year-and-a-half. When I first went on it, I had really bad side-effects.

I didn’t sleep much [and] I felt really sick a lot of the time. I didn’t want to talk about it at work, so I had to just keep going in every single day. Had I been physically unwell, I would have told someone – but because I was so scared, I lost the right to do that.

I want to live in a world where everyone can talk about mental health and it’s 100 percent okay.

Hope Virgo

What does ambition mean to you?

Constantly pushing myself to be better at what I’m working on, whether it’s my job, my own personal development, or in my recovery.

Do you think having had anorexia changed what some of your priorities were in terms of ambition?

Maybe more so recently. I went through a phase of my recovery where I was just this functioning anorexic person, who was a healthy weight but I still counted all my calories. I still exercised a lot and struggled a bit with my mood. But now I’m at a point where actually I don’t want to be that person, I don’t want to have the restrictions around food. When I go out for dinner with people, I want to be able to have what I want off the menu and not always to pick a salad. Because that’s really boring.

I want to live in a world where everyone can talk about mental health and it’s 100 percent okay. There’s a worry for me that, at the moment, everyone is talking about mental health and it’s amazing – but in six months’ time, it might not be the most sexy thing to talk about. Because of what I’ve been through, my goal in life [is] to make sure that people are talking.

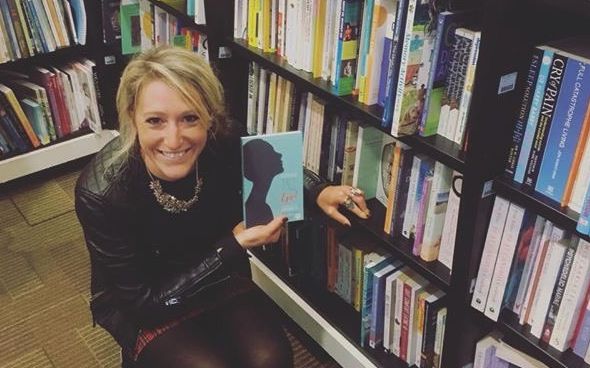

Hope Virgo with her new book. Image Credit: Hope Virgo / Twitter

Do you think that we’re having a useful conversation around mental health as a society?

I think it definitely helps but I still don’t think it’s enough. We’re doing all this talking but there’s not enough action being done by government, by the NHS. If we want to make real long-term change, we have to get going. I think that people shy away from the less well-known mental health problems – people don’t think about things like psychosis as much.

Sometimes, with me, when I talk about my recovery, I don’t talk about the extent of it – like I don’t have loads of my back teeth because of my eating. My body was in a really bad way, but we don’t talk about that much because it’s not glamorous, it’s not cool. So, I think it’s about keeping this conversation going, but actually taking it one step further as well.

I’m not a believer anymore. I do believe in something, I’m just not quite sure what.

Hope Virgo

Are you a believer, atheist or agnostic?

I used to go to church when I was younger then I stopped when I went to hospital and then didn’t go back. I really struggled with the fact that I didn’t feel like the church was able to answer questions on why I’d been unwell. It baffled me that I was asking these questions, and no one really had the answers. So, I’m not a believer anymore. I do believe in something, I’m just not quite sure what.

What is the meaning of life?

I think to build relationships and to love people and be loved back. I love meeting new people and hearing people’s stories. So, for me, it really is just about having those relationships – that will give you an amazing life if you want it to.