Human rights are often headline news. A celebrity asks a court to protect their privacy from prying tabloids. The government withdraws legal aid from refugees, so they cannot afford to claim asylum. But do we know where human rights come from? What underpins them? Do they apply to all of us – are they universal?

In the first part of a two-part series, Helena Kennedy QC takes a step back from the headlines and asks some fundamental questions about human rights. What are their origins? Do they have the moral authority that human rights lawyers and campaigners seem to take for granted? This is not just about law, but the bigger picture: the philosophical and historical foundations of human rights.

Are human rights universal?

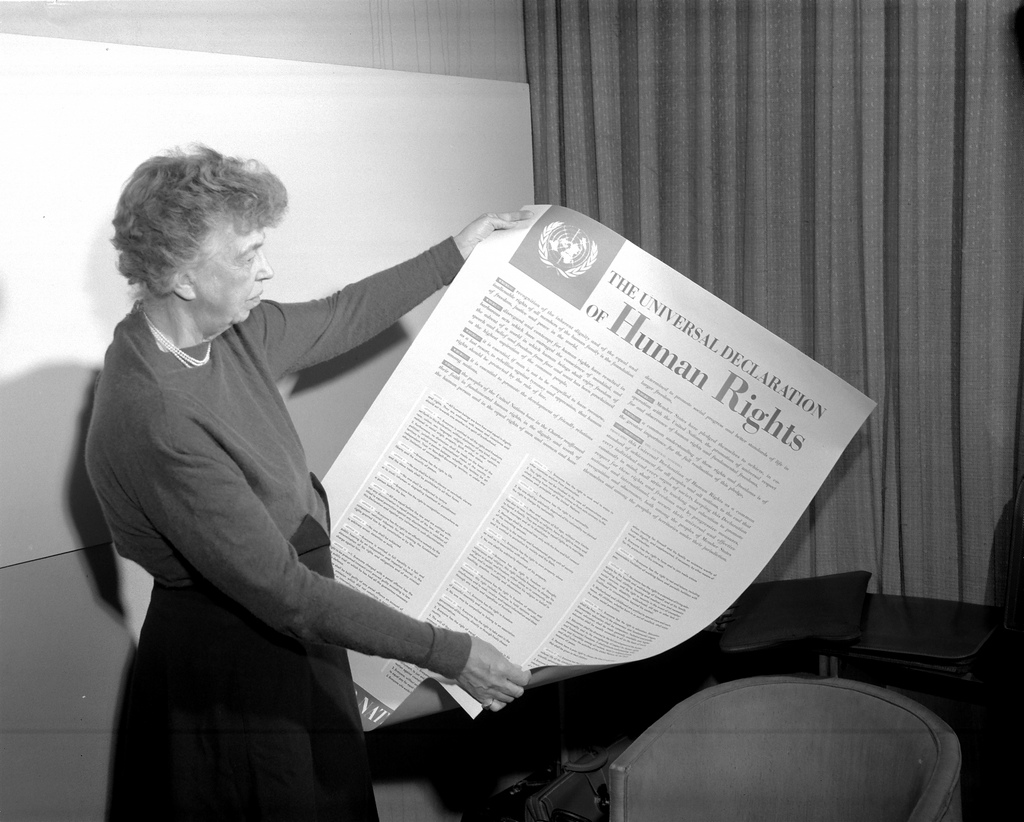

Eleanor Roosevelt holds a poster of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights at the United Nations

The programme’s starting point is the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that “recognition of the inherent dignity and … equal … rights of all … is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world”. The programme explores whether human rights can really be universal – whether there was any truth in the claim that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was “A Bill of Rights for the human race”.

Kennedy asserts that the authority of human rights lies in the fact that they apply to everyone. But we all know they don’t in practice. “They are universally broken”, as she says. So why should we expect these rights to be adhered to above religious ideas, political creeds and ideas of the common good?

Kennedy discusses these questions with guests, including barrister and legal academic Professor Philippe Sands QC; historian and author of The Last Utopia: Human Rights in History, Professor Samuel Moyn; and historian Dr Faizal Devji. Can we claim a shared sense of humanity that underpins rights? Are human rights a western political invention? The legal story is one thing, but it is the philosophical story that we are concerned with here.

Where do human rights come from?

Cyrus’s Cylinder – thought by some to be the ‘first charter of human rights’

Dr Irving Finkel, a distinguished curator at the British Museum, discusses Cyrus the Great, an enlightened King of Persia from the 6th century BC, who is credited with the creation of the ‘first charter of human rights’.

Cyrus understood the importance of benign and enlightened government. Kennedy asks: is this fundamentally what human rights are for? Her answer seems to be yes. There are ideas, in both ancient western and non-western worlds, of brotherly love and common enterprise. Are these translated into today’s language of human rights, as a secular replacement for religious values?

Barrister and legal academic Professor Conor Gearty argues that we must resist the temptation to pick and choose from history to justify our belief in human rights. Today’s language of human rights reflects commitment to democratic governance, dignity and the rule of law, which are reflected in many ancient cultures, though they were not necessarily called human rights advances at the time. These are threads – persistent, universal threads – across the world, says Professor Gearty.

Only universal on paper?

There is much debate about whether it is possible to attribute rights to humans simply by virtue of their humanity. Perhaps this idea is just a legal or political fiction, since rights are not equally realized and many states ignore abuses when addressing them would be difficult. This leaves Kennedy with the “disconcerting” question: are human rights only universal on paper?

Kennedy accepts that human rights are not universally applied in the world. But she concludes with her belief that the existence of human rights draws on a shared meaning of being human. She sees universal, common threads within civilizations – ideas like respect, fair ruling and tolerance. She believes that these provide the moral underpinning for the idea of universal human rights.

Kennedy’s discussion is captivating in its pursuit of ancient threads and opens up profound questions about why rights are so inconsistently protected across the modern world.

You can catch up with part one of Are Human Rights Really Universal? on the BBC Radio 4 website. Part two will air on BBC Radio 4 at 8pm on Monday, 25 May 2016.

Share this post if you think human rights belong to everyone.

Learn more about what human rights do for all of us with RightsInfo’s resources.