Facebook has played a “determining role” in stirring up hatred against Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar, according to the United Nations (UN).

According to the team of UN human rights experts investigating the alleged Rohingya genocide in Myanmar, the way people are using Facebook has substantively contributed to spreading hate speech and acerbating violence against “the world’s most persecuted minority“.

For its part, Facebook says there is no space for hate speech on its platform, and they’re working with experts to develop safety resources for people in Myanmar and counter-speech campaigns.

“This work includes a dedicated Safety Page for Myanmar,” they told the BBC. “A locally illustrated version of our Community Standards, and regular training sessions for civil society and local community groups across the country.

“Of course, there is always more we can do and we will continue to work with local experts to help keep our community safe.”

What is Going On With Rohingya in Myanmar?

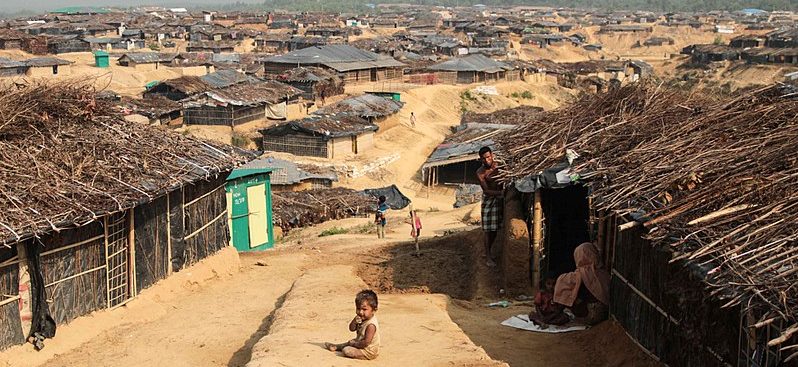

A Rohingya refugee camp in Bangladesh. Image Credit: EU Echo / Flickr

The Rohingya have existed in Myanmar for centuries. They have been living in the country, formerly known as Burma, for as long as they can remember; and yet they have never been allowed to call it home.

The Rohingya – a (mostly) Muslim ethnic group trying to put roots in a Buddhist majority country – have indeed always been perceived and treated as aliens, outcast from society and subjected to persecution and violence. In 1982 they were stripped of their citizenship and became a stateless people.

In the following years, hundreds of thousands of Rohingya people fled to Bangladesh in order to escape persecution and violence at the hands of the Burmese army. Those who did not flee were confined to the northern portion of the Rakhine state, isolated in their villages or displacement camps and effectively sealed off from the rest of Myanmar.

Confined to what is effectively an open-air prison through a vicious system of institutionalised discrimination and segregation.

Amnesty International

Things have continued to deteriorate, and violent attacks in October 2016 and August 2017 sparked an intense crackdown. Massive “clearance operations” have been going on ever since, with Rohingya villages being burned to the ground and survivors telling brutal stories of murder, rape and torture. Harrowing evidence documents the scale of the massacre.

Nearly 1 million Rohingya have fled to Bangladesh so far. However, things are not easy for Rohingya refugees. Living in sprawling camps, they constantly struggle to get their basic needs of food, water and sanitation met, and are exposed to patterns of abuse (such as forced child marriage and trafficking).

Furthermore, the beginning of the monsoon season is expected to further deteriorate living conditions for Rohingya refugees. Despite this, living in precarious conditions in Bangladesh remains a much better option than being returned to Myanmar, which is still far from safe. Many have thus called for, and ultimately obtained, the postponement of any repatriation of Rohingya refugees.

Are We Witnessing a Genocide?

Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Myanmar. Image Credit: United Nations Photo / Flickr

In September 2017, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra‘ad al-Hussein, described the situation as “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing”. More recently, he said that it may constitute genocide, but many academics have been saying this for some time now.

A UN fact-finding mission on Myanmar – which was prevented from entering the country by the Burmese government – is pointing to strong evidence of crimes under international law that must be collected and presented to the international criminal court. The international community has been repeatedly criticised for remaining silent and not doing enough to stop the unravelling tragedy.

In the meantime, Myanmar has always rejected all allegations of ethnic cleansing or genocide, and it reiterated this rejection last week. It has also been reported that the Burmese government is now considering new legislation that would seek greater oversight of the work of international non-governmental organisations, including the UN.

What is The Role of Facebook in All of This?

Image Credit: Pexels

Image Credit: Pexels

The UN investigators have said that Facebook played a significant role in stirring up hatred against Rohingya Muslims. They noted that the platform is especially ubiquitous in Myanmar and a key channel for spreading racial hated across the country.

Facebook has become the sort of de-facto internet. It has turned into a beast.

UN Investigators

According to many commenters, as well as a recent study, Facebook has been a powerful vessel of vitriolic propaganda aimed at (further) vilifying the Rohingya, with a host of Facebook pages – including that of the ultra-nationalist monk Ashin Wirathu – relentlessly spreading hate speech. Furthermore, researchers have noted how the government’s and military junta’s monopoly on information has created “a digital space that bolsters coercion”.

Millions of Myanmar citizens have unlimited access to low-cost internet on their mobile, but the “open information pipeline” remains dangerously one-sided, exposing “Facebook’s dark side of self-reaffirmation with limited perspective”. In this context, anti-Rohingya content “goes viral, normalising hate speech and shaping public perception. Violence against [the] Rohingya people is increasingly welcomed and then celebrated online”.

‘The Facebook of Things’

Evgeny Morozov has been looking into the dark side of the Internet for some years. Image Credit: Re:publica / Flickr

In other words, Facebook is accelerating violence in Myanmar, but more worryingly, it’s not the only global example. Across the world, Facebook is being questioned about its expanding role and responsibilities as a publisher of information and a data holder.

In Britain and the United States, there are investigations looking at the spread of misinformation on social media in the context of the ‘Brexit’ referendum and the 2016 USA presidential election. The Cambridge Analytica data scandal has demonstrated the scale of the phenomenon, with whistleblower Christopher Wylie revealing that 50 million Facebook profiles were harvested by the data analytics firm, with political targeting aims.

Dictatorial regimes across the globe – from the Arab Spring countries, to Russia and China – have now learned to master digital technology. Propaganda is vital to authoritarian regimes, and censoring social media is now the norm (think China and Turkey). Facebook, in particular, has come under fire for its collaboration with Rodrigo Duterte, the ruthless Philippine president. Researcher Evgeny Morozov, author of The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom, see this all as a clear warning – the internet can help feed the power of dictators.

It’s not the only view, however. There was a time when the internet and Facebook were saluted as pathways for freedom and democracy. During the early weeks and months of the Arab Spring, “talk of technology and revolution were inseparable” and Wael Ghonim, one of the leaders of the Egyptian revolution, was quoted as saying “if you want to liberate a government, give them the internet”.

In a time where technology is moving an ever-increasing pace, it’s difficult to know just how social media will affect our lives in the future. It’s clear both Facebook and other platforms have both huge potential for good and bad – it’s how we manage this in the next few years which is crucial.