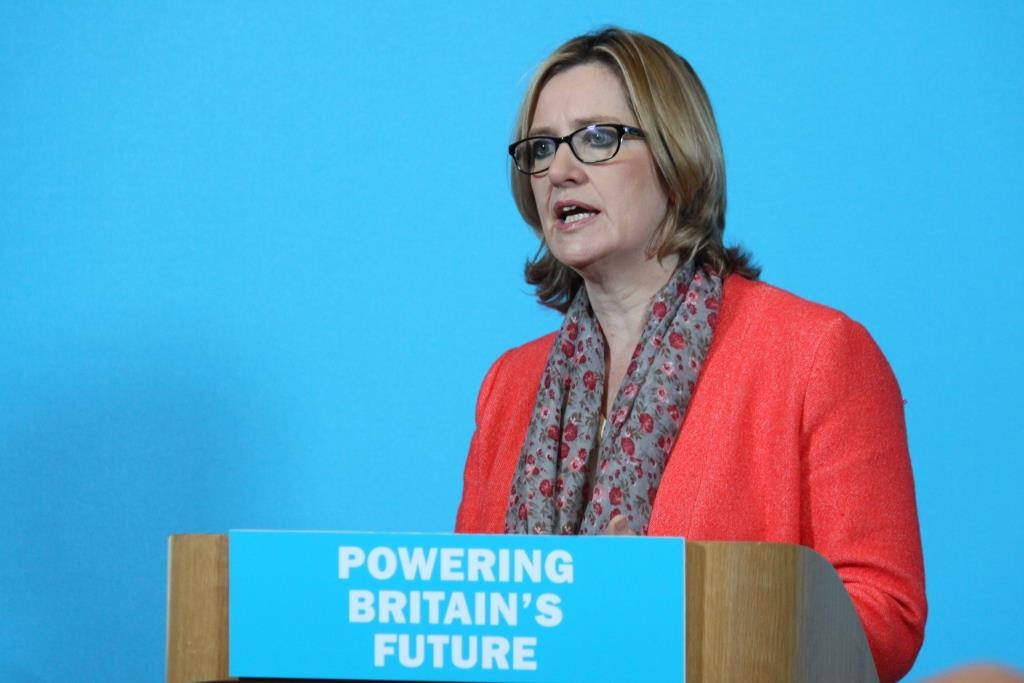

The work and pensions secretary, Amber Rudd MP, has conceded that the government’s flagship welfare reform, universal credit, contributed to the nationwide rise in emergency food aid use. The admission comes after a series of denials from various government ministers who claimed that this was not the case.

In August 2018, The Guardian reported that senior Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) officials had been tasked with overseeing a study to investigate whether the government’s own policies were actually to blame for the sharp rise in food banks.

While a junior work and pensions minister, Damien Hinds MP said that he did not expect the further rollout of universal credit to mean more people having to use food banks.

Alok Sharma, another junior minister in the DWP, also stated that there were many complex reasons for people using emergency food aid that were not linked to universal credit.

Speaking in parliament this week, Amber Rudd MP recognised that delays in payment have meant that people have “had difficulty accessing their money early enough“ and, furthermore, that this was one of the causes “of the growth in food banks.”

When it was first introduced, there was an automatic six week waiting period for any new claimant to universal credit. Rudd, the former home secretary, pledged a more humane approach to the benefits system after taking the DWP job in November.

Answering to ministerial questions in the Commons about food insecurity and universal credit this week, she added: “I believe and hope that the changes we have made in terms of accessing early funds will have reduced insecurity”.

A Rocky Rollout

Research released by the Trussell Trust in October 2018 showed the use of food banks had increased by 52 per cent in areas where universal credit had been in place for a year or more. This compared to 13 per cent in areas where it had not been.

In Amber Rudd’s own constituency of Hastings food bank use went up 80% after UC rollout in 2016.

The research does not stand alone in its criticism of universal credit, with Citizens Advice finding that people on universal credit were more likely to be in debt than those on legacy benefits.

At the end of a visit to the UK in late 2018, Professor Philip Alston, the UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, described universal credit as “gratuitous, cruel and counter-productive.”

“The rationales offered for the delay are entirely illusory, and the motivation strikes me as a combination of cost-saving, enhanced cashflows, and wanting to make clear that being on benefits should involve hardship. Instead, recipients are immediately plunged into further debt and inevitably struggle mightily to survive.”

In last year’s budget, Chancellor Phillip Hammond announced more funding to help the troubled welfare reform, pledging an extra £1bn for universal credit with the aim of cutting the waiting times from 5 weeks to 3 weeks.

‘Drastic Changes Needed’

Image Credit: Flickr/World Skills UK

Image Credit: Flickr/World Skills UK

The new benefits system has come in for persistent criticism and was supposed to be up and running by April 2017. It is now not expected to be fully operational until December 2023.

The DWP has said that, under universal credit, people are moving into work faster and staying in work longer.

Sabine Goodwin, Independent Food Aid Network Coordinator, says “the roll-out of universal credit has been forcing claimants to use food banks for years,” however.

Responding to Amber Rudd’s comments this week, she continued: “The work and pensions Secretary’s admission of a link between the new benefit and food bank use is welcome but falls short of the drastic changes needed.”

“Advance payments are in fact loans which reduce payments when they finally come and those supported by a 2-week extension of legacy benefits still have 3 weeks to wait. Much more needs to be done to improve a system that is putting too much pressure on those who can least afford it.”

Our right to food is protected by a number of international standards, including Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights.

States are required to “progressively” realise the rights enshrined in the ICESCR. Unlike the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which requires states to immediately realise the rights enshrined in the treaty, states are required to ensure economic, social and cultural rights (such as the right to food) only “to the maximum of its available resources.”

gratuitous, cruel and counter-productive

UN special rapporteur Professor Philip Alston on Universal Credit

End Hunger UK research with front line providers of emergency food aid found that there were four key reasons that people either applying for or in receipt of universal credit were being forced to turn to their services: excessive waiting times; delays in receiving payments; debt and loan repayments; and benefit sanctions.

People in food poverty often have high levels of stress and depression, with poverty being both a potential causal factor and consequence of mental ill health. People with a disability or a mental health condition are far more likely to receive emergency food aid than any other group.

Articles 25 and 28 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which the UK has signed and ratified, stipulate that states have a duty to provide people with disabilities with an adequate standard of living and the highest attainable standard of health.

Children have special provisions, such as those in Article 24 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, to protect their right to food, as child malnutrition can result in serious long-term health consequences.

Where Next For Universal Credit?

Image Credit: JJ Ellison / Wikimedia

Image Credit: JJ Ellison / Wikimedia

We should never accept that there are households across the UK that do not have enough money to put enough healthy food on the table.

Many governments around the world are already taking positive steps towards the progressive realisation of their citizens right to food, thereby committing to ensure that healthy food is an entitlement rather than a luxury.

Our changes to Universal Credit mean more people get more support, helping them into work and off benefits.

We made these – extending advances, cutting waiting times – because there were issues with the initial roll-out of UC. I‘ve been clear about this since I took over at DWP.

— Amber Rudd (@AmberRuddUK) February 11, 2019

“We are committed to a strong safety net where people need it,” said the work and pensions secretary in parliament this week, continuing, “we have made changes to accessing universal credit so that people can have advances, so that there is a legacy run-on after two weeks of housing benefit, and we believe that will help with food and security.”

Since taking on her role at the DWP, Rudd has paused the planned mass move of existing benefit claimants to universal credit, with another trial now being planned. The minister has also introduced changes such as making payments directly to women if they are the household’s main carer.

Labour has called for ministers to halt the roll-out “as a matter of urgency”.

Just Fair Policy Director Koldo Casla believes the government “had turned a deaf ear to the evidence” but that “it is never too late.”

“It is time to revisit the fundamentals of our welfare state as a source of collective pride, as an inspiration for a more equal society, as a matter of human rights.”