Myanmar claims to have repatriated the first Rohingya refugees. But the British Rohingya Community say such actions are futile without a permanent political solution for their people. Lucy Milburn speaks to members of the Community about the genocide, life in Britain, and their campaign to help family, friends and fellow Rohingya left in the refugee camps.

Over a million Rohingya, the ‘world’s most persecuted minority,’ have now fled their native Rakhine State for Bangladesh, following what some have called a genocide of their people.

It’s a complicated story, with the latest news seeing Myanmar announce the return of the first refugee family in a new repatriation programme. But Bangladesh has disputed the claim, arguing that the family never crossed to Bangladesh in the first place. The action has been criticised as a publicity stunt orchestrated by the Myanmar authorities to distract from what the UN have branded “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing”.

The British Rohingya Community Responds

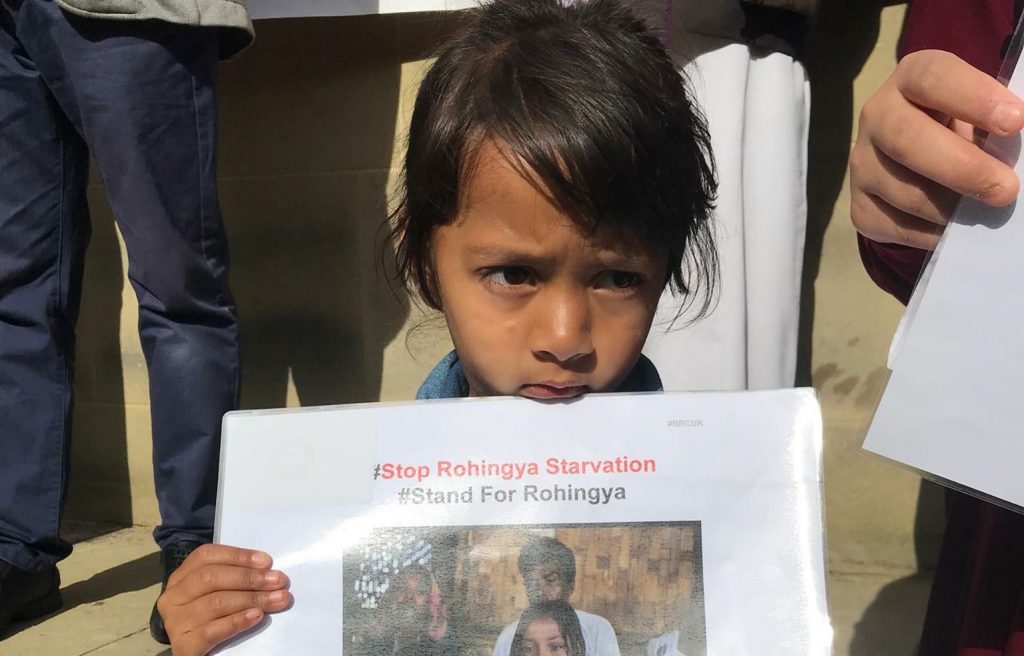

A demonstration by the group. Image Credit: The British Rohingya Community / Facebook

A demonstration by the group. Image Credit: The British Rohingya Community / Facebook

In the UK, the British Rohingya Community (BRC), based in Bradford, are outraged by what they call the “fake news” of the premature repatriation. The conditions that forced the Rohingya to flee have not been addressed and safe resettlement is not possible when their villages no longer exist and unregulated violence continues.

With 400 members, the BRC is the largest community of Rohingya people in Europe. In 2008, many Rohingya arrived in the UK via the UN’s Gateway Protection resettlement programme. Although immensely grateful for the opportunity to start a new life, they are desperate to help their relatives, friends and fellow Rohingya who remain in refugee camps in Bangladesh.

“The Refugee Camp Was An Open Prison”

Kutupalong Refugee Camp. Image Credit: DFID / Flickr

After spending 18 years in the Kutupalong refugee camp, Nur Huda, chairman of the BRC, has lived in Bradford since 2008. He recalls the appalling conditions of the camp, and how the Rohingya were dehumanized and deprived of their dignity and fundamental rights. There was no freedom to move around, no access to healthcare or education and they faced a constant struggle for food, water and sanitation.

“When I arrived in Bradford, I began to feel like a human being,” he says. “I’m not scared anymore. I’m not persecuted anymore. I’m not unwanted anymore. We have everything that humans need to live here. Our children go to school and college. Even in our own country, there was no chance to be educated over primary [level]. We could not go to other villages without permission.”

Women are facing rape. There is child abuse, villages are being completely burned down, innocent people are being killed.

Nur Huda, Chairman of the British Rohingya Community

Nur now dedicates six days a week to working for the organisation, supplementing his income with night shifts as a taxi driver. Nijam Uddin Mohammed, general secretary of the BRC, also divides his time between the Community and jobs as both a taxi driver and an interpreter for the NHS. Every Monday, they hold a meeting for the entire community.

“We are all from different parts of Burma, we have different contacts so we get different news from each other. We make a report and discuss what is happening in each village.”

“We Are Dismayed For Our People”

Nur (middle) works in the evenings so he can run BRC. Image: The British Rohingya Community / Facebook

Nur (middle) works in the evenings so he can run BRC. Image: The British Rohingya Community / Facebook

Through its ‘Stop the Genocide’ campaign, the BRC has been lobbying politicians and contacting unions in their efforts to “bring perpetrators to justice.” UN human rights officials say ‘crimes under international law’ may have been committed in Myanmar and have called for evidence to be collected and presented in international criminal courts.

“We are dismayed for our people,” Nur says. “Women are facing rape. There is child abuse, villages are being completely burned down, innocent people are being killed. We are always worried for our people.”

Last October, a delegation from the BRC returned to the camp in Kutupalong to deliver food, medicine and other donations from the wider community. Nijam discovered that his parents’ village had been burned to the ground, a tragedy which steeled his resolve to fight for his people’s rights.

A Struggle For Human Rights

Aung San Suu Kyi. Image Credit: Comune Parma / Wikimedia

The BRC are doing everything in their power to achieve a “political solution” for their people. In 1982, the Rohingya were stripped of their citizenship and they are now stateless, unwanted by both Myanmar and Bangladesh. The BRC are demanding that the Rohingya are reinstated as citizens of Myanmar with their dignity restored and their human rights recognised.

“The Rohingya people never fight for a separate country– we always fight for our rights,” Nijam explains. “If we get full citizenship and the full rights that other people have, then we are happy.”

If we get full citizenship and the full rights that other people have, then we are happy.

Nijam Uddin Mohammed, General Secretary of the British Rohingya Community,

The BRC’s anger has been stoked by the response of Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s state counsellor and de facto head of government. In what has been called the “clearest act of complicity,” the Nobel Peace laureate and formerly celebrated human rights icon, has failed to condemn the horrific events.

“We had a great expectation for her,” Nijam explains. Following her house arrest after the 1991 election, the Rohingya actively campaigned for Suu Kyi’s release when they came to the UK. “We travelled to lots of cities, we spoke with the MEP, local politicians and the universities. We believed that if a democratic government came to power, then she would look after the people of the country.” Now, however, they feel betrayed.

“Education Is the Backbone Of the Nation”

Nijam Uddin Mohammed. Image Credit: British Rohingya Community / Facebook

Nijam Uddin Mohammed. Image Credit: British Rohingya Community / Facebook

The Community are concerned that, without substantial education, the Rohingya will eventually be forgotten. “The government in Myanmar are trying to wipe out the Rohingya from history,” Nur argues. “Education is so important. As Nelson Mandela said: ‘education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.’”

“Our goal is to promote cultural activity,” Nijam agrees. “We want to raise awareness about what’s going on in Myanmar and the history of the Rohingya. If our children’s generation forget the history of the Rohingya, then we are finished.”

If our children’s generation forget the history of the Rohingya, then we are finished.

Nijam Uddin Mohammed, General Secretary of the British Rohingya Community

Nijam and his brother Sirazul, who achieved 4 A*s in his GCSEs despite arriving in the UK unable to speak English, are starting this awareness raising campaign close to what is now their home, here in the UK. The brothers recently spoke to thousands of teachers at the National Education Union Conference in Brighton and they gained the support of the National Teacher’s Union to continue their campaigns.

“We must do something for our children in the refugee camp – there are more than 400,000 children,” Nijam says. “As a consequence of the genocide, there are already nearly 40,000 children without parents, who need education.”

With the approach of monsoon season, which could result in enormous deaths among Rohingya refugees, the need for a political solution for the Rohingya is more urgent than ever.